Understanding how a voice disorder can impact your relationships

When anyone develops a vocal disorder that impairs their ability to effectively communicate, they may experience depression and find themselves socially isolated as a result of their vocal limitations. They may also experience financial instability because the condition may impact their career or ability to get a job. This disorder, if not carefully navigated, can also impact the personal relationships of those living with the disorder, including their spouse, children, parents and friends.

Your voice is a part of who you are

Since the voice is a signature part of who we are, it can affect your self-image. And as much as we may not want to admit it, our view of ourselves is shaped by how others see us. The book, Easier Done Than Said, Living with a Broken Voice by Karen Adler Feeley, includes this quote from someone living with spasmodic dysphonia (SD).

“Individuals look at you like you’re crazy. They cannot understand what you are saying. If your voice is shaky, you are immediately classified with low self-esteem, no confidence, nervous, and not taken seriously.”

At the onset of a disorder that impacts your ability to communicate, like SD, you have to navigate and refine your role with family, friends, coworkers, members of your community and your medical team. You must reconstruct many of your social behaviors and navigate to your new normal. In lay terms, you have to adjust and come to terms with what has happened to your voice and it can have a great impact on the personal relationships that are so important to you.

Let your family support you!

More importantly, you need the support of those around you to make navigating this loss easier.

How your family and friends can help you through the stages of adjustment

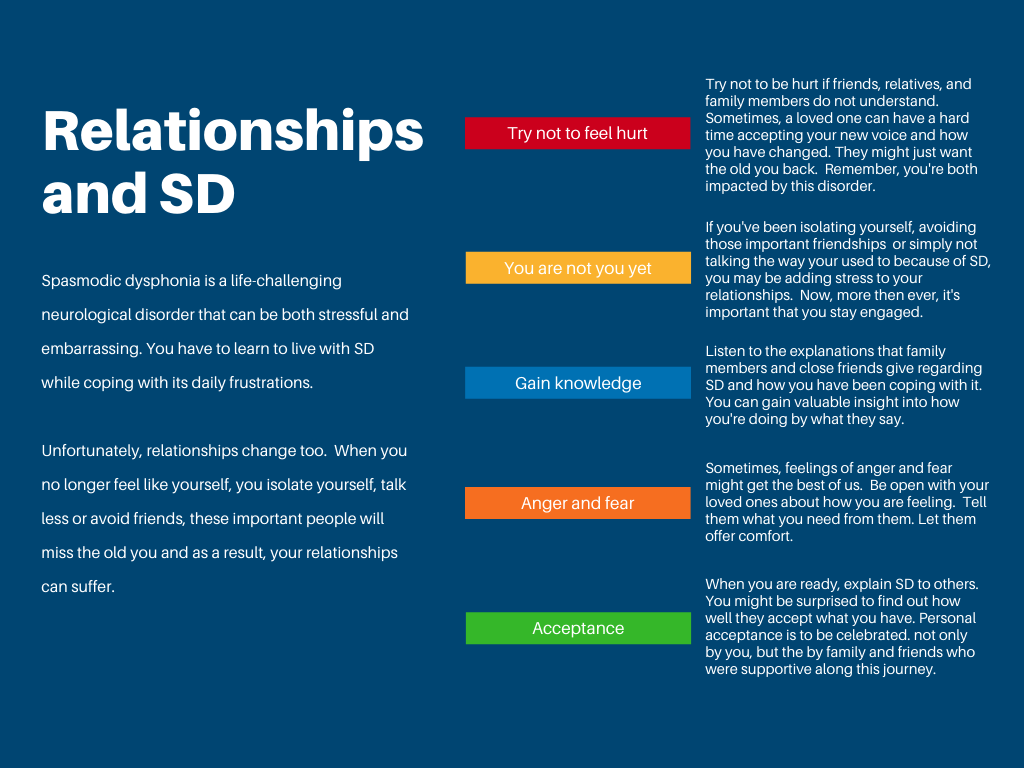

A major change, like the onset of SD, any vocal disorder or any disability for that matter, means that the person will likely be struggling with what is happening to them. It is also likely that they will undergo a series of stages of adjustment until finally reaching acceptance of what has changed before they can fully thrive. These stages are normal and acceptable; however, they are not neat and orderly. People progress through the stages at different paces and may skip stages altogether. The following discusses each stage and provides guidance on how family and friends can provide support.

These stages are normal and expected, however, they are not neat and orderly. People progress through the stages at different paces and may skip stages altogether.

Stage 1: Recognition and Depression

Your loved one is in a state of numbness, both physical and emotional. Something is wrong. They are asking themselves, what’s going on with my voice. This stage can wreak havoc with a person’s self-esteem.

As a person runs through this gamut of emotions, those that they love, friends, family, and coworkers are also struggling. Living with someone who is going through depression and isolating themselves from people can wreak havoc with the family dynamics. Suggestions on how you can help during this stage:

Address your concerns. Talk about their emotions, how it is impacting the family unit and remind them that you are there to help them.

Support them. Spend time together, offer positive ways of thinking about the future. Continue to socialize.

Cope with the change. Help them find proper diagnosis. Search for doctors and answers with them. Provide reassurance that they are still important to you. Update key people (family, friends) about what is going on.

Stage 2: Relief

Nothing helps a person move beyond the depression stage more quickly than the correct diagnosis. Once a person has a name to call it, they can start to arm themselves with answers and potential treatments for symptoms. As a family member or friend you can:

Celebrate the fact that now there are answers. Enjoy the good spirits that flow with new knowledge about what is going on.

This is real. Reinforce the fact that this is a real medical condition and nothing to feel embarrassed or depressed about.

Let them talk. This might be the first time that talking about the condition flows easily. Try not to interrupt or finish their sentences for them, they need to feel you are listening.

Stage 3: Anger and Sadness

Typically, the person diagnosed with SD will enter the anger/sadness stage when they realize that this condition does not go away, is not curable, treatments may not work consistently, and because SD is rare, that it does not get attention for research. As a friend or loved one of someone in this stage it is important to provide the following:

Offer patience and support. Continue to offer support. Be patient with them and listen when they talk. Never assume how they feel. You currently lack credibility because you do not have the disorder.

Get the person in touch with others affected by the disorder. They know what it is like to walk in the person’s shoes. It is important that they see that this disorder does not define who they are and doesn’t have to impact their entire life. Support groups are a great starting point.

Be a distraction so the problem doesn’t intensify. It is easy to obsess and slip into self-pity. Your best support may be to get the person out and active, putting a pause on thinking only about SD. This “time away” from the disorder can help build a more positive attitude.

Stage 4: Denial, Fear and Shame

Your friend or loved one is having thoughts about how others may think less of them, how they are different from the rest of the world, and that their job security may be in danger. This sense of fear/shame doesn’t just hit the person living with SD one time, but every time they try to speak. As a result, this stage lasts the longest and getting beyond the fear or shame may not fully happen at all.

For family and friends, this is a really difficult stage. When the our organization surveyed those with SD about advice to family and friends, the responses ran the spectrum. Some said help us, others said don’t help too much. Then there was the talk to us about SD and do not talk about our voices and do not treat us differently but remember we have a disability. This is as confusing for you as it is difficult for them. So our advice is this:

Try not to be surprised or upset by unexpected reactions. Since everyone’s SD is different and everyone’s reaction to getting the diagnosis is different, and moods change from day-to-day, the best thing you can do is ask them what you can do to help. When they ask for help, drop everything and help. Their needs may change, but knowing that they can count on you when they need support is the best thing you can offer.

Illustrate your own acceptance of their disorder. Support them when they try different options for treatment, research the disorder and offer insight and never comment on the sound of their voice. Saying “your voice sounds better today” can be construed as “it usually sounds worse.” Someone going through this denial, fear, and shame roller-coaster could see this as a negative.

Do not talk for them (unless asked). They are trying their hardest, and do not want to be marginalized. Nothing illustrates your acceptance more than when you are a patient and engaged listener.

Stage 5: Acceptance

Once a person starts talking about their disorder, they are moving closer to acceptance. This step is important because the best part is the freedom and relief that they will feel. They will stop thinking or even obsessing about the condition and stop worrying about how others perceive them and their self-confidence grows. Unfortunately, a person can slip back into old ways of thinking and become sad again. Time is a really important element in the cycle. As time goes on, the sadness appears less often and the times of acceptance and confidence become longer. For the family and friends, enjoy this stage; you’ve waited a long time for it.

Encourage them to have fun and enjoy life. Schedule some fun activities to lengthen the cycle of acceptance, especially in the beginning.

When they slip back, do fun things. When they lose their spirit, push for more time pursuing activities they enjoy. It will help get them back to a positive state quicker.

Stage 6: Advocacy

As Linda Friskey, someone living with SD, wrote, “Advocating for yourself is part of acceptance”. Advocating for a cause requires a person to recognize that a problem needs fixing. In order to increase awareness and research, the stories need to be heard. It means talking about the disorder and the physical, emotional and financial struggles faced. It means super-acceptance and is a very powerful position emotionally. Their story will help others dealing with the disorder. For the family and friends of someone who has reached the advocacy stage, be proud of them.

Recognize their accomplishment. While you accepted them, they did not accept themselves, and now they are. Celebrate that.

Encourage them to advocate. Help them by making sure they can carve out the time from a busy daily life to help others with the disorder. Babysit, wash the dishes, whatever they need so that they have the opportunity to “pay it forward” as they say.

Advocate along with them. It is a powerful statement to your loved one when you say, “I accept you, and the disorder, and want to make sure your voice is heard.”

Validation is key

“When a loved one comes to you for support, the number one best thing you can do is to clearly validate their feelings. Validation is an acknowledgment and recognition of another person’s thoughts, feelings, and perspectives. It doesn’t mean that we have to agree, but if we care about the other person, we do need to explicitly accept how they see the situation and their reaction to it”. 1

Validation is “the simplest way to convey the most important messages of emotional support – I see you, I understand, I care about you, and I’m here for you. What does explicit validation look like? It may be as simple as looking someone in the eye and saying, “I understand how upsetting that would be.” Other examples include: 2

Don’t give advice unless asked

You’re job is not to fix the problem, they are in the process of turning to you for emotional support. Do not offer advice, downplay the significance of how they feel or make them feel inferior by telling them what they should do. Instead, ask questions, listen attentively and validate their feelings.3