Singer, Songwriter Kristina Stykos

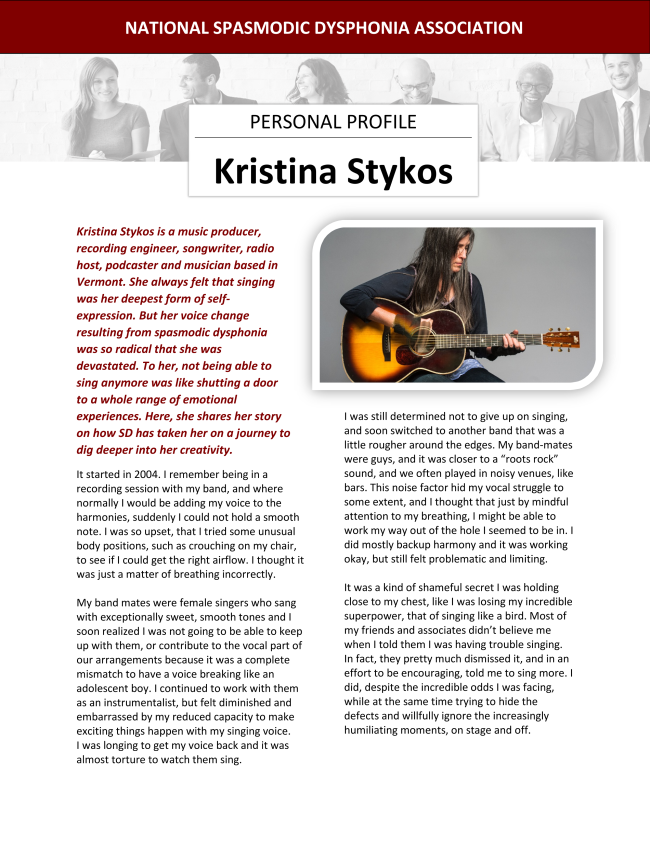

Kristina Stykos is a music producer, recording engineer, songwriter, radio host, podcaster and musician based in Vermont. She always felt that singing was her deepest form of self-expression. But her voice change resulting from spasmodic dysphonia was so radical that she was devastated. To her, not being able to sing anymore was like shutting a door to a whole range of emotional experiences. Here, she shares her story on how SD has taken her on a journey to dig deeper into her creativity.

It started in 2004. I remember being in a recording session with my band, and where normally I would be adding my voice to the harmonies, suddenly I could not hold a smooth note. I was so upset, that I tried some unusual body positions, such as crouching on my chair, to see if I could get the right airflow. I thought it was just a matter of breathing incorrectly.

My band mates were female singers who sang with exceptionally sweet, smooth tones and I soon realized I was not going to be able to keep up with them, or contribute to the vocal part of our arrangements because it was a complete mismatch to have a voice breaking like an adolescent boy. I continued to work with them as an instrumentalist, but felt diminished and embarrassed by my reduced capacity to make exciting things happen with my singing voice. I was longing to get my voice back and it was almost torture to watch them sing.

I was still determined not to give up on singing, and soon switched to another band that was a little rougher around the edges. My band-mates were guys, and it was closer to a “roots rock” sound, and we often played in noisy venues, like bars. This noise factor hid my vocal struggle to some extent, and I thought that just by mindful attention to my breathing, I might be able to work my way out of the hole I seemed to be in. I did mostly backup harmony and it was working okay, but still felt problematic and limiting.

It was a kind of shameful secret I was holding close to my chest, like I was losing my incredible superpower, that of singing like a bird. Most of my friends and associates didn’t believe me when I told them I was having trouble singing. In fact, they pretty much dismissed it, and in an effort to be encouraging, told me to sing more. I did, despite the incredible odds I was facing, while at the same time trying to hide the defects and willfully ignore the increasingly humiliating moments, on stage and off.

When I started to lose my range and ability to shape vocal tones as a singer, I still had all this energy that had formerly been engaged in the technical, emotional process of making sound. That energy, that raging desire to communicate from the depths of the heart, had to find a way to get out and make art. So, I kept returning to my laboratory (the recording studio).

I started to learn how to do recording engineering. The impetus to do this was directly related to my wanting to continue to explore singing, but without the pressure of anyone else hearing me. I’d been a songwriter since the 4th grade, and was not about to stop my creative flow. So, I began to record myself, and was able to work with my vocal issues in the studio, to get good results. Not the results I felt I was truly capable of, but results that reflected the reality of where my voice seemed to be taking me.

I expanded my knowledge of how sound works and how I could engage not only my voice, but other instruments and mixing techniques to get the message across. The power and passion of what I feel will never be limited by equipment, vocal or otherwise.

My husband did not believe that my vocal problem was “real”. It was towards the end of our marriage when I first noticed my speaking voice starting to weaken. He would call across the house to me, and I literally could not respond. There was a block there when it felt like my voice was completely refusing to cooperate with the life I had been living.

A couple years after our divorce, I was at a low point. I was desperate to get out of my psychological hole and also face the fact that drinking alcohol was ruining my health and not solving any real problems. So, one day, I quit cold turkey. It was in the weeks and months after quitting booze that my speaking voice took a turn for the worse. Or more likely the removal of alcohol and self-medication allowed the condition to reveal itself in full.

When it got to the point of not being able to order a sandwich at Subway, I knew I needed to get help. My mother had been diagnosed with spasmodic dysphonia a couple of decades earlier and even had Botox® injections, so I knew I was probably facing the same diagnosis. But when it was finally confirmed, I felt much better because, at last, I was validated. Up to that point, everyone seemed to think I was having some kind of confidence issue that was affecting my voice. It was kind of like when you’re told: “just get over it”.

I did an intensive 3-day session with a speech therapist who treats the condition holistically and who has it herself. The time I spent with her gave me the encouragement I needed to forge on. After having hit rock bottom and reaching the point of feeling hopeless, I was truly terrified that there might come a day when I would not be able to speak at all. She kept coming back to these important words that I have not forgotten: “You have a voice”.

It has not been easy. Every single day I have to overcome the desire to simply go mute. It often seems easier to stop talking than to listen to my voice struggle. Obviously finding ways to use my voice musically has taken a huge amount of effort and totally re-routed my career. But equally challenging are the smaller diminishments, such as not being able to make simple phone calls.

This is still a place where I freak out and have a hard time and I have definitely been depressed and anxious about my handicap. But over time, I have had to take a more philosophical approach. I would not be the first person to have a disability or malady of some sort. It’s actually pretty normal to confront physical challenges in life. This one is hard to hide, and it has its particular way of causing embarrassment, but only to the extent that you continue to let it.

Since then, I have learned to put my panic to the side and take constructive steps to stay on track with my life and career. Having been a professional singer, I have very much taken my own steps to work with my “different” voice. My therapist gave me tips and exercises, but mostly I make up my own, following her lead. But knowing she is there when I fall, and that she totally gets it, is crucial to my daily peace of mind.

The more you put yourself out there and make the effort to talk, the less isolated you are. I have utilized the mechanisms of my life to stay in the mainstream of human activity as much as possible. Co-hosting a radio show is something I continue to do, despite how I sound on a bad day. People give me a lot of room to be as “unique” as I am. My fans have not been so aware that my vocal changes were due to any condition. They probably just thought I was drinking a lot of whiskey and going through some hard knocks in my life.

But now it’s out there and now, after a couple high-profile feature articles, the news is out, and I am officially an SD poster child. I might have faked it longer, but what’s the point? I have discovered in my speaking voice, a base line “authentic voice” that I arrive to now and then, where there is very little stress or strain. I try to reinforce that voice when it is available to me. I feel there are deep emotional and even deeper spiritual issues that really run the show underneath SD.

The conditioning of the brain to arrest the flow of communication has roots that can be found and also mysterious underpinnings that can only be guessed at. Part of the journey with this condition, for those who can find the wherewithal to detach from the trauma and who are inquisitive about such things, is to ponder the heart and how it has been blocked and silenced.

Having SD puts your vulnerabilities on your sleeve and even though a lot of those vulnerabilities were there all along, with SD you feel exposed against your will. Most people who encounter my vocal issues do just fine. It’s really incumbent on me to find the self-compassion to handle myself properly when called upon to speak, and not get overly discouraged when things don’t go well or as planned. Hiding my own self-doubt and fears from my kids used to be very important to me. Now it’s more about modeling to them how one deals with a disability gracefully.

I get the most support from friends who have taken the time to listen to me, and who can see the efforts I’m making to stay in the current of my life and not isolated. A longer conversation in a relaxed setting with an empathetic ear allows my voice to come forward more fluently, and this is critical for the healing process.

SD has taken me on a journey to dig deeper into my creativity. My creativity is not dependent on only one avenue or medium. Memories of singing are a touchstone. I had to adjust some of my hopes and dreams, and come up with something equally exciting but more realistic. Now my dedication for developing my writing is even more stoked and inspired.

On my CD, River of Light, some of the basic vocal tracks were recorded earlier in my vocal decline – or change, to put a more positive spin on it – so you can hear more melodic information in some songs, than in others. I’m also working on a book of poetry and expect to publish it within the year.

In some funny way, I’ve had to get “louder” and stand up for myself with more vehemence and conviction. I think in some of us with the condition there was already a tendency to melt into the scenery and not speak up. Now, if I want my voice to function at all, I have to really want to speak and consciously will myself into voicing my opinion. My new voice often seems too dramatic or accentuated with energy, but maybe I was playing it too safe before and hiding behind my voice. Now there are no sweet smooth tones to hide behind, or charm others with, to get their approval. I have to show up, in a more raw, honest form.

I doubt I’ll ever sing on a stage again, but in the recording studio, I’m still exploring what I can do with a lot of patience and perseverance. Getting into headphones and committing to working with your voice in that setting is a challenge for someone with SD but you’d be amazed at what you can do.

You just have to get over your horror at what you can’t do, and start focusing on what you can do. I sometimes have to do 50-75 vocal takes to get what I want but it’s worth it. It’s still a lot of fun and if you have something to say, there is no better time to say it than now.

I bring many things to the table when producing other artists but most certainly I bring compassion for any struggles they may be having with their voice, be they struggles of confidence or technical struggles. I want people to feel supported and that any way they are feeling or any sound they’re making is valid and accepted under my roof. I also have high standards musically, so I gently push to get what I see might be their highest potential. Then I find ways to technically focus in on what’s working with a little judiciously applied editing and mixing.

Hanging on to the things that I’ve loved to do but just transforming how I do them, has been key to retaining my identity and vitality. I always look for “the wave” which I can catch when my identity is most fully engaged and 100% behind my communication. Following your bliss is very important for people with SD. There is no time better than now to dive deeper into the places where your heart is full of passion and strength. The voice will find a way to follow and heal.

To those who are working with this condition, I’d say give yourself room to be pissed off about it but when you’re ready, face it head on and don’t let it cripple your dreams. The whole experience is bound to open doors: in terms of feeling deeper compassion for yourself as well as understanding the struggles of others. This increased awareness makes for a life worth living and well lived. Life is, after all, what happens when you are making other plans and that’s true for everyone, not just people with this condition.

You can listen to Kristina’s music on Spotify and SoundCloud and learn more about her at: http://kristinastykos.com/